Anti-rape campaign #ThatsRape ④

By Ye-ji

Published March 8, 2016

Translated by Marilyn Hook

|

Editor’s note: The Korea Sexual Violence

Relief Center is leading a campaign against sexual assault committed with the

help of alcohol or drugs, called #ThatsRape. This 5-part series of articles

explores the discussions held by the campaign’s planning committee, as well as

their questions and recommendations for change.

User reviews of “seduction

drinks” and aphrodisiacs

In one episode of tvN’s popular drama Cheese in the Trap, there is a

university student who is “famous” for giving younger female students alcohol

until they black out and then taking them to a motel. Though several women have

been the victim of this, he still enjoys a trouble-free student life.

The drama’s female lead also finds

herself very drunk after drinking the alcohol that he provides. Just when he is

helping her out the door, the story turns trite by having the cool male lead

appear and help her evade the danger. The male student, angry at this

obstruction(?), raises his voice and asks, “Why are you sending away a girl who’s

been seduced?” The male lead replies, “If you want to find a job and not end up

a bum, you’d better watch yourself.”

|

A scene from episode 3 of tvN’s Cheese in the Trap

|

If the student had taken a woman too drunk to consent to a motel and had sex with her, it would have undeniably been rape. But he considered it mere “seduction” and is infuriated that the male lead got in the way. And the male lead doesn’t point out that this is criminal behavior, but merely quietly threatens him by saying he needs to worry about the future that his debauched ways will bring. And what about the female lead? Appearing naïve and innocent, she is put in a taxi hailed by the male lead, without knowing anything, without saying anything.

Reality is not much different. One thing

that I’ve felt as one of the organizers of #ThatsRape, a campaign against sexual

violence committed with the help of alcohol and drugs, is related to common

beliefs about sexual relations that happen after alcohol or drugs have been

ingested.

Sex that happens without your partner’s

consent, that uses alcohol or drugs, is clearly rape. And yet, alcohol is

treated as merely one way of seducing someone into dating or sex, or as a

lubricant that makes a relationship smoother.

Of course, alcohol can make a

relationship closer, and pleasurable sex can accompany it. The problem is not

drinking alcohol or having sex in itself. It’s the context: the who, how, and

why. Having sex after you’ve given an unsuspecting partner drugs or strong

alcohol - the victim’s experience of this act is being ignored and the

perpetrator’s view that “alcohol is a useful means of seduction” is gaining

dominance.

That stories about taking a woman to a

hotel with the help of “seduction drinks,” as well as reviews of purchased aphrodisiacs

that are illegal because of worries that they cause sexual crimes, are passed

around without shame show the terrible situation in which rape is misnamed “seduction.”

Not forcefully

resisting equals consent?

If there is a different between this

drama and reality, it’s that [in real life] the victim has a chance of taking the

perpetrator to court. But reality becomes even darker at that point. In court,

the prosecuting side and the defending side wage a fierce battle over the

truth.

Here, the law is not the same as the

truth. It is a tool for seeking or approaching the truth. It cannot become the

truth. We expect the law, which appears absolute, to be just and impartial, but

of course it is a cultural and historical product of the society of the people

who make and enforce it. Verdicts can never be free from social discourse and

values.

If you look at the “Act on the Punishment of Sexual Crimes and Protection of Victims

Thereof” and interpretations of it, the blind spots of law as a product of

society become vividly clear.

Article 297 of the Criminal Act states

that those convicted of rape “through violence or intimidation” are to be

sentenced to a minimum of three years in prison. However, Korea’s Supreme Court

has taken the position that the degree of violence or intimidation is “the

degree to which one’s partner’s resistance is impossible or noticeably

difficult.” Because of this, the focus of sexual assault cases becomes whether

or not the victim was able to resist. That is, the complainant has to prove how

difficult (impossible) it was for her to resist what was happening, or how

strenuously she did resist, in order to be recognized as a victim.

Sexual assault that takes place when the

victim is unable to resist because of alcohol or drugs is punishable under

Article 299. Rape or molestation when the victim is unconscious or unable to

resist is classified as quasi-rape or a quasi-indecent act by compulsion. But

the standards for unconsciousness or inability to resist are not clear.

Accordingly, it is easy for mistakes based on the court’s interpretations and

arbitrary decisions to occur. Just as a rape verdict is based on the

complainant’s ability to prove how hard she resisted, quasi-rape requires her

to prove her inability to resist, and similar incidents end up with completely

different results based on the judge’s interpretation. This shows that the

relevant article is failing to act as a basis for clear-cut judgments.

|

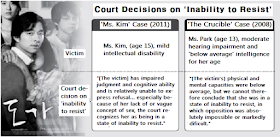

| Translated graphic from a 2011 Dong-a Ilbo article |

The above graphic was used in the Dong-a Ilbo article “Court Rules

‘Intellectually Disabled Who Don’t Refuse Sexual Advances Still Considered

Unable to Consent’”, published on Nov. 6, 2011. It compares court decisions on

the sexual assault of a 13-year-old hearing-impaired girl at Gwangju Inhwa School,

known as ‘The Crucible case’[1], and

the sexual assault of a 15-year-old girl with an intellectual disability that

the perpetrator met through a chatroom. These two incidents clearly show how

arbitrary courts’ interpretations of the ‘inability to resist’ are.

In a courtroom

in which all sorts of circumstances and evidence are flying about, the

complainant and defendant end up battling over whether the sexual act was based

on ‘agreement’. However, the two Criminal Code articles mentioned above force the

decision about ‘agreement’ to be based on proof of how desperately the victim

resisted or how weak she was. It’s a system in which rape isn’t defined on the

basis of mutual consent, but decided by the manner (through the perpetrator’s

violence or threats, or the victim’s unconsciousness or inability to resist) in

which the sex act takes place.

These laws make cognitive dissonance

unavoidable. What’s more, ancillary elements unconnected to the incident

itself, such as the victim’s everyday conduct, sexual preferences, and even her

gait when she is drunk, become the basis for a verdict. In a situation in which

sex is determined to have been consensual because the complainant didn’t fully

resist, the meaning of ‘consent’ is being understood in a distorted way in our

society.

All sex without

consent is rape

In the USA, until 1970, unwanted sex was

only recognized as rape when the victim put up ‘utmost resistance’ by

physically fighting the perpetrator. But with the rise of the rape reform

movement most states scrapped this requirement, beginning with Michigan in

1974. (Reference: “Not fighting desperately means ‘yes’?”, Chosun Ilbo, Jan. 8, 2011)

Also, a 1992 decision handed down by the

Supreme Court of New Jersey took the position that sex without consent is

sexual violence, saying that sexual penetration that takes place without the

victim’s active, freely-given permission constitutes sexual assault.

(Reference: “Stereotypes and fact about sexual assault”, Dong-a Ilbo, Nov. 11, 2014)

Similarly, Article 265 of Canada’s

Criminal Code stipulates that sexual acts that occur without one’s partner’s

consent or through the use of direct or indirect force are crimes. Of course,

this too leaves room for debate over the interpretation of ‘consent’. The article

goes on to describe situations in which consent is impossible: when one side

feels threatened or afraid, or can’t easily resist the exercise of authority.

When consent becomes the establishing

factor for the crime of rape, the victim’s ‘inability to resist’” cannot be the

standard by which sex that takes place under the influence of alcohol or drugs

is judged to be rape. All evidence and circumstances are instead restructured

and interpreted on the basis of the question of whether, in a situation in

which the victim could consent, clear and mutual consent did in fact exist.

The difference in the criminal codes of

South Korea and North American countries boils down to different answers to the

question of what rape is. If in the latter, rape is ‘all sex without consent’,

in our society, it’s ‘sex with violence, threat, inability to resist, or

unconsciousness’. The countless types of pain that are left out of this

definition but exist in real life are outside of the reach of the law, becoming

the burden of individuals.

But simply adding behaviors that

constitute rape to the law doesn’t guarantee that the problem will get better,

because our lives are much more complicated than a few lines of legal code. I

mean that the few acts that the law covers being considered rape cannot lessen

the unique pain of each person in our society. In order to bring victims’

suffering into the reach of the law, we don’t need to list the prerequisites

for rape, we need to give shape to what rape isn’t: sex based on clear consent.

In other

words, if we clearly answer the question of what isn’t rape with ‘sex that I

consent to’, all other sexual acts are rape. What must be changed is the very

definition of rape that forms the basis for our scream of #That’sRape.

*Original article: http://ildaro.com/sub_read.html?uid=7396

[1] After a 2009

novel and 2011 film (also known as Silenced)

that depicted it and related incidents.

No comments:

Post a Comment