“Underlining in the Bookstore” Series: Kim Hyejin’s Counsel Culture

By Dalli

Published: February 7,

2023

Translated by Julie Leigh

Series

Introduction: With a strong conviction that women's voices, whether in writing

or speech, deserve a more resonant presence in the world, I carefully curate

books for inclusion on the shelves of my bookstore, Salon de Mago. By

underlining words in these selected books, this series aims to impart their

essence and flavor to readers.

“When it came

to words, she had never felt fear. She was confident that she perfectly

understood the world of words… Then she realized that, amidst the abundance of words,

she had been squandering unnecessary ones. She had never considered how her

words lived once released into the world, or where they eventually died.” (Kim

Hyejin’s novel Counsel Culture p. 225)

|

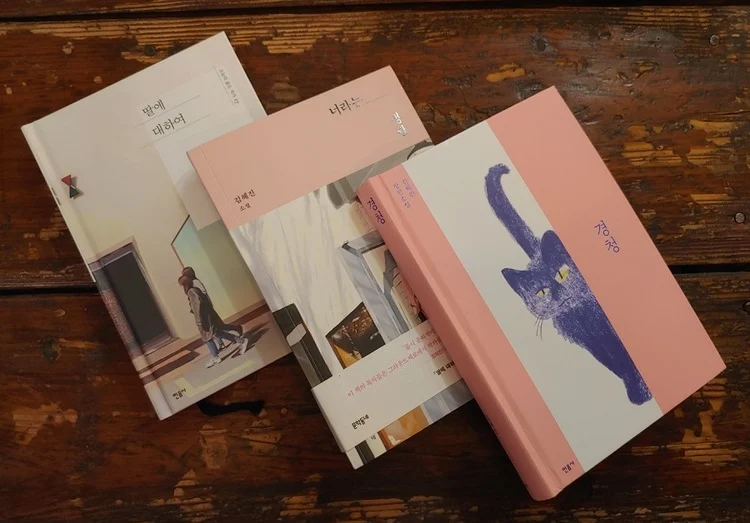

| Kim Hyejin’s novels stored in Salon de Mago: Concerning My Daughter (2020, Mineumsa), The Lifestyle that is You (2020, Munhakdongne), and Counsel Culture (2022, Mineumsa). © Dalli |

While reading an online New Year’s fortune-telling site, I came across the advice “be careful not to get involved in gossip,” and my heart began to race. Being a target of gossip is something I go to great lengths to avoid. While it’s said that even malicious comments at least show that someone is paying attention, I’ve come to realized that certain forms of attention can feel like a kind of violence. Even for someone whose livelihood depends on getting attention, the destructive impact of harsh criticism and abusive language is undeniable.

Some

time ago, my casual words, after being taken apart and pieced together by

others, were spread across social media. When someone asserted that they were

hurt by my words, it felt like a knockout blow. Faced with collective scrutiny

and judgment, I surrendered entirely, just waiting for the nightmare to pass.

After that

incident, I went through a prolonged period of suffering, caught up in fear within

my relationships with others. Self-blame, resentment, self-reflection, and a

sense of injustice all tangled together, keeping me stuck in the complex traps

of the past—where everything had gone wrong in the first place. Eventually, I

chose not to keep digging into the hurtful memories and decided to cut ties

with both the incident and the people involved.

If you

found yourself being scrutinized by the public or tangled up in a relationship

misunderstanding, what would you say? It seems like in those moments, people want

assertions rather than conversations. If only loud and assertive statements

counted, the truth would be solely measured by the volume of one’s voice and

genuine intentions might be drowned out. Some people who are convinced they’re

never wrong end up becoming downright merciless toward those they think are

wrong. Trying to convince such people, who are incapable of conversation, that

you’re being treated unfairly seems pathetic and even pointless. Are we fated

to keep going through this harsh cycle of misunderstandings?

“She always let herself be guided by words, wandering until she inevitably got lost. She didn’t mind losing herself in this way. It was during those nights, scrolling through her smartphone and computer screen, that she grasped the potent impact a few words or a simple sentence could have, piercing straight to her heart. On those nights, each moment felt like a painful repetition, as if she were being stabbed.” (p. 65)

After Haesoo, the protagonist of Counsel Culture, becomes the

subject of public scrutiny, she finds herself unable to openly express her

stance or emotions to those around her. For nearly a year, her only outlet is

writing letters—each filled with words she struggles to articulate aloud. These

letters, initially polite and reserved, drift into a mix of resentment and

explanations, concluding abruptly and inconclusively. Haesoo reads and revises

these letters repeatedly to search for the precise words to convey her

feelings, yet each night, she ends up tearing them apart, unable to send any. “Is she an unforgivable perpetrator or a

victim, falsely accused?”

In her thriving

15-year career as a counselor, Haesoo has achieved such success that she

becomes a regular guest on a TV program. Enjoying her well-established life,

she never questions her ability to manage her emotions and words. However, when

she makes a negative comment about a celebrity who later commits suicide,

Haesoo loses both her friends and job. She is then condemned and ridiculed, slapped

with the label “the counselor who killed someone.”

Exiled

from the world, Haesoo often takes walks at night, when she can conceal her

identity. During one such stroll, she unexpectedly comes across Sei, a

10-year-old girl trying to help a sick stray cat named Sunmu.

“Breaking things is always easier than

building them. If life is like building blocks, she's realizing that removing

just one piece can unravel the whole structure. And she's surprised at how valuable

insights like this are everywhere, common enough to be a dime a dozen.” (p.

156-157)

|

| Kim Hyejin’s novel Counsel Culture (2022, Mineumsa). © Dalli |

Haesoo always believed in her

communication skills, but a single remark shatters her life, leaving her

trapped by formidable barriers of words from those around her. Eventually she

can’t even compose another letter. As the familiar world of words crumbles,

so does her sense of direction in life. However, through interactions with

Sunmu, a stray cat expressing herself in a language beyond words, and Sei, a

10-year-old speaking openly without self-censorship, Haesoo discovers a new way

to connect. In the process of “interpreting, explaining, challenging, agreeing,

and confessing” in her relationships with these two, Haesoo, who “once assumed

she could understand everyone”, finds unexpected reassurance. The dynamic

conversations between the characters vividly illustrate that care is not a

one-way street.

“It’s strange.

The unspoken exchanges with Sunmu provide her with a sense of reassurance. In a

world filled with clamorous words, she’s never experienced anything quite like

it. Understanding, empathy, reassurance, and acceptance—are these feelings only

achievable in complete silence?”

(p.224)

Haesoo throws herself into the task of rescuing

Sunmu, treating it as if it’s a way to pull herself out of a swamp. However,

she grapples with a persistent question—whether this might be a form of

self-pity. Similarly, in Sei’s case, Haesoo suspects that Sei is being bullied

by her classmates. Still, out of respect for Sei’s reluctance to accept

assistance, Haesoo approaches only as far as Sei permits. This attitude, where

Haesoo refrains from completely immersing herself in her role as a caregiver

and maintains a certain distance, must be a characteristic of the author, Kim

Hyejin. The theme of “distancing” persists throughout the novel, offering

insights into what the author considers caregiving and ethical awareness

towards the vulnerable.

While

it’s common to seek solidarity in relationships forged through shared

suffering, genuine understanding of and responsibility for one another cannot

solely stem from a mutual experience of pain. This reality is evident in Sunmu’s

case; having lived on the streets, “risking everything in fights she might lose”,

the cat initially distrusts Haesoo, the one setting a trap for her rescue. The

eventual coexistence of Haesoo, Sei, and Sunmu becomes achievable only because,

as Haesoo realizes when deciding to move on from her own past struggles, true

connection emerges not through shared suffering but through goodwill and compassion.

Sei complains to Haesoo about always losing at dodgeball, calling it dumb. Haesoo replies, “You can always start the game over. You learn more when you lose.” After deciding to face and accept her past struggles, Haesoo stops writing letters to let out her feelings. Instead, she chooses to listen more carefully. The time of paying attention begins.

“As a counselor, Haesoo discovered time and again that

many people carried wounded and fragile hearts. The

realization of this truth would not be possible without the support of goodwill and

compassion. Perhaps, this understanding was the only thing left to her—the sole

remaining essence that she hadn't lost. Is it possible, then, to say that she

succeeded in preserving it? Is it?” (p. 296-297)

Writer Introduction: Meet Dalli, the co-owner of Salon de Mago, a local

bookstore and cultural space in Namwon, North Jeolla Province. She's not only

the author of the essay “I Write What My Body Speaks” (2021) but also the

creative mind behind women’s writing programs such as “Quiet Liberation: The

Writing Journey to Find My Own Voice” and “How to Write to Fill the Gaps in

Life.”

*Original article: https://m.ildaro.com/9555

No comments:

Post a Comment