Shutting Down the Red-Light District: Stories of the People of Yongjugol Facing Eviction

Published

Feb. 1, 2024

Translated

by Anastasia Traynin

On

Monday, January 29, 2024, people who had been ordered to demolish the buildings

inside Paju’s Yongjugol red-light district began to appear, part of the second

execution by proxy (a type of gangjae

jiphaeng, an administrative execution often referring to forced demolitions

and evictions) carried

out by Paju

City Council. It had been two months since the first demolition attempt took

place on November 22 of last year. The problem is that there are still people

living here in Yongjugol.

Paju’s Yongjugol emerged in 1953 as a military camptown (kijich’on) providing sexual services to US Army soldiers after the end of the Korean War. At one time, it was a flourishing area, known for being the country’s first camptown. This was made possible by permission from the state. In 1961, the Korean government officially made the sex trade illegal through the “Anti-Prostitution Law.” However, in 1962, 104 red-light districts and camptowns were designated as “special areas,” where selling sex was tacitly permitted.

The organization Anti-Prostitution Human Rights Movement E-loom documented the closing of the Cheongnyangni red-light district in the book Cheongnyangni: Systematic Forgetting, History Linked by Memory, which explains the historical condoning of the camptown sex industry.

“In

principle, prostitution inside the red-light districts was illegal, but apart

from a few cases, there was never an actual crackdown by the authorities. In

fact, the women working inside the red-light districts had to undergo regular

testing for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) by the government. This

specific policy toward Korea’s sex industry is referred to as the ‘Tacit

Permission and Management System.’”

Paju’s

Yongjugol was also one of the places affected by this “tacit permission and

management system.” Even after the US Army left the area, Yongjugol continued

as a red-light district.

As of

today, around 50 establishments and 85 sex workers continue to operate in

Yongjugol, and they have been fighting demolition and eviction since last year [2023].

Many citizens have been calling for their voices to be heard and for people to take

interest in the issue.

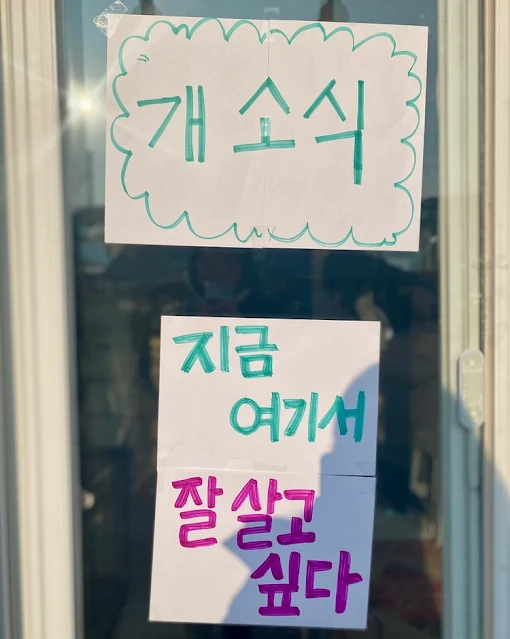

In the

afternoon of January 29, the “Opening of the Yongjugol Sex Worker Defense

Sit-In” was held for those in solidarity with the struggle against the ongoing eviction

process. For around 1.5 hours, supporters heard from Byeolli, representative of

the Yongjugol sex worker association Jajak Namu Hwae (literal translation:

White Birch Society), about the situation in Yongjugol and the diverse stories

of the people living and working here. The event was facilitated by Yeoreum, an

activist with the organization Sex Worker Liberation Action Movement Scarlet

ChaCha.

These

stories are about people’s lives that don’t fit into the simple dichotomy of

being for or against prostitution. Before evicting and pushing them out,

shouldn’t people at least listen to their stories? Here, I share the stories

told by activist Byeolli during the opening event.

2023 Paju Mayor’s New Year Address Began the “Shutting Down

Yongjugol” Project

Last year, on January 2, Paju mayor Kim Kyung-il announced the Red-Light District Maintenance Plan in his first official document of 2023 and formed an exclusive task force with the aim of “shutting down Yongjugol within the year.”

“The day the mayor made the announcement, I was getting a consultation on whether or not to trade in my car. I said I would think some more about putting down the contract fee and walked out of the shop. That’s when I heard that the mayor had announced that he would get rid of Yongjugol. Actually, they’ve said that so many times, I didn’t think anything would happen. But this time it seemed like the mayor was serious and there would be a problem. So it would have been really bad if I had traded in my car.” (laughter)

Though

there was talk of installing a shipping container at the entrance of the

neighborhood to serve as a base for authorities, it initially wasn’t considered

as a serious problem. After the Paju

mayor’s announcement, the women workers who until then didn’t know each other

well formed the Jajak Namu Hwae association. Since submitting a petition to the

city and meeting with city council members a few times, they thought the issue

was being resolved. Then the container was put in, and news came that the task

force had been formed. Finally, the

workers set up a meeting with the task force when it came to visit Yongjugol.

“There

were members of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and public

officials, so we thought they would help us. But as we talked, women who had

come to Yongjugol from Suwon (the Suwon Station red-light district was

completely shut down in 2021) must have figured out what was going on, and they

got angry because they had experienced being kicked out of a [forcibly] closed

red-light district. So they argued back that even though the government

promised support, if it was really supporting the workers, why did only 30 out

of 200 people in Suwon receive benefits, and why did people from there end up coming

here?”

People Whose Lives Aren’t Reflected in the Victims of

Prostitution Rehabilitation Ordinance

Paju

City Council announced that it would support the women workers of Yongjugol

through the “Victims of Prostitution Rehabilitation Ordinance,” and it would be

for an “unprecedented” two-year period, unlike the usual one year provided by other

local governments. Yet the women workers do not welcome these benefits. The

reasons for this can be found in the fine print behind the pledge of providing

up to 40 million won.

|

| An early morning last September in Yongjugol, before the proxy execution. Photo by Ilda. |

According

to the “Relocation Compensation Measures Package” put together by Jajak Namu

Hwae in preparation for the meeting with the Paju mayor in August of last year,

the affected community has identified three main issues. The first is that out

of the roughly 200 workers that were counted in Yongjugol in early 2023, only

100 would be eligible for benefits through the ordinance. How could a program

that offers support to only half of those affected ever be trusted?

The

second problem is the lack of overlapping benefits. For example, if worker A is

a recipient of 500,000 won through the nationwide basic livelihood subsidy, she

is only eligible to receive a matching amount of support through the ordinance,

instead of the original 1 million won. In other words, while basic livelihood

subsidy recipients, single parents, and others receiving welfare benefits are

also eligible to apply for ordinance benefits, the total amount they could

receive is reduced.

The

third problem is the fact that the ordinance itself was created without any

input from the affected community. The condition for receiving support through

the ordinance is restricted to those signing a “memorandum to exit the sex

industry,” and any evidence of engaging in prostitution would result in having

to return all or a portion of the funds.

In the

case of housing benefits, the recipient must live in a place designated by Paju

City Council for up to two years, and Jajak Namu Hwae points out that the

living expense subsidy (1 million won per month for one year) does not consider

the reality of housing costs. Not only that, but there are people in Yongjugol

whose lives are outside of the scope of this ordinance.

“Honestly,

as this situation (closing Yongjugol) has continued for over a year, there are

a lot fewer people coming here. Still, there are many different reasons why

women stay. For one thing, there are many single moms in Yongjugol, so when

you’re raising kids, it’s not easy to move to another area. They’d have to move

schools, it’s complicated. Also, those who were driven out of Suwon and other

places don’t want to go through that again. I’ve also been here for 10 years,

and it’s hard to imagine going somewhere else.

There

are also the relationships here. Some of the women don’t have parents or

families, so the people whom they’ve worked and struggled with here have become

family. Especially the aunties who make us food. They’ve worked here a long time,

so they ‘care a lot about the girls (us),’ they say. There’s even one auntie

who’s doesn’t just make food and go home, but who waits for us to eat after we

wake up. She’ll watch us eat and say, ‘Eat this, eat that.’ Even if I say,

‘I’ll eat on my own,’ she keeps saying,

‘Eat this.’ It’s

such a burden. (laughter)

Actually,

many women working here are on medication for mental disorders or disabilities.

They have mental problems caused by childhood trauma and other issues, so they

really can’t live a normal lifestyle. Some have illnesses like epilepsy, so

they can’t go to an average workplace. There are many who didn’t graduate high

school and those who spent their lives only working and looking after their

parents and brothers, who now pretend not to know them. Others got divorced

with no settlement money or child support so they have no choice but to support

themselves. Now (that I’m active in Jajak Namu Hwae), I’m also learning about

their lives.”

Are We Who Live in Yongjugol Not “Citizens”?

The plan to shut down Yongjugol within the year proceeded with installation of the shipping container at the neighborhood entrance, weekly Tuesday tours by outsiders walking for a “happy street for women and citizens,” and attempts to install CCTV cameras throughout the area. The container, which was supposed to be a place for counseling the workers and hearing their stories, instead came to be used for police surveillance, and the weekly tour made them feel like spectacles. It was the same for the CCTV. No one welcomed the idea of installing cameras in front of their homes and places of business.

“About

a week after last November’s eviction attempt, they tried to install another

CCTV camera. Instead of coming through the neighborhood entrance and down the

road, they cut through a nearby field with the crane to try and take us by

surprise. It was around 6:30 in the morning, and they didn’t even bring in

police for mediation or in case of an accident. Though most of the residents

are women, there were no female police officers or public officials.”

Due to

fierce resistance by Yongjugol workers, the camera was not installed that day,

but a worker who protested by climbing up an electric pole and onto the crane

claw sustained physical and psychological injuries. Actually, a construction

worker mounting an excavator to install a CCTV camera is in itself a violation

of Article 202 of the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Act, which

states, “When working with claw-mounted construction equipment, workers are not

permitted to be in any position other than the seat of the vehicle.” Byeolli

remembers this day as “the day an illegal act was committed against us

‘illegal’ people in Yongjugol.”

|

| One of the signs hung in the sit-in space during the opening reads, “There’s no feminism that expels women’s lives.” Photo by Ilda. |

There Are Others Working in Yongjugol

Establishment

owners and sex workers are not the only two kinds of people in Yongjugol. There

are also kitchen aunties, laundromat aunties, beauty salon ladies, and uncles

working in the marts and convenience stores. Everyone has a role to play here.

Yet the “shutting down Yongjugol” project does not consider them, let alone offer

them support.

“Sometimes

I think about giving up (the fight against eviction), but there are too many

people involved. Recently, I met a salon lady who told me her shop isn’t doing

well, so she’s had to take on the second job of making house calls to do

people’s hair. I asked her if she’s okay, since it could be unsafe to go to

strangers’ places, and she just replied, ‘Well, I have to work, so I have to

go.’ The laundromat auntie can’t even bring herself to ask us for the laundry

money. There’s no work, so the girls say apologetically, ‘I’ll give it to you

next month, Auntie,’ and she just says, ‘Take your time.’ I heard there’s even

an auntie who insists on getting only half of her monthly pay from the owner.

These

aunties are almost all in their 60s and 70s, and most of them have lived in

Yongjugol for 40-50 years. Though it’s not the case for everyone, [some] people who have

been working here for a long time have enough money [to stop working].

But they want to continue working here. At their old age, they can’t do other

kinds of work, and their lives, friendships, and relationships are all here. If

their jobs disappear, they’ll have nothing to do, no one to meet, and no people

to care for. They ask ‘Where will I go?’ It’s terrible for them to think of

just staying home all day.”

These

elderly aunties in their 60s and 70s are also participating in the struggle, as

well as the mart uncles. Even though Yongjugol is their longtime home and

workplace, Paju City Council has no current countermeasures planned to support

them when it is shut down. What makes them the angriest is being “treated as

nonexistent people,” with no contact other than the sudden announcement of

shutting down within a year. They have no idea what they should do to prepare

and are asking, “Can we really just be ignored like this?”

There Are People Still Living Here

“There’s

a grandmother who comes here to collect boxes [to earn money from recycling facilities].

We called her ‘Foul Mouth’ because she would come around and swear all the

time, and every time she saw me, she’d ask for a cup of coffee or a cigarette,

so I didn’t really like her (laughter).

She would gather up so many boxes that she couldn’t carry them all, so we

thought, ‘What’s wrong with her?’ But then she donated 500,000 won to our

association. We wondered how this grandmother could spare the money, and we

hurried to try and return it to her. It turns out that she’s a former ‘Yankee

princess’ [yang gongju, a common name

for women who provided sexual services in the US military camptowns]. She used

to work in the camptown and remained in the neighborhood. So she gave us an

extra 500,000 won to use for our struggle. It was really touching.”

From

the outside, Yongjugol might be seen as just a place that should quickly

disappear and have its history covered up. However, the fact that there have

been people making their livelihoods here for a long time cannot be forgotten.

Is it really too much to ask to allow them a bit more time and to put together

a proper relocation plan? The people of Yongjugol are also aware of the reality

of their situation. All they are asking for is sufficient communication,

relocation measures, and time to prepare for their next steps.

On the morning of January 30, Paju City mobilized public officials, police, the fire department, and demolition service workers [yongyeok, often referred to as “thugs” or “goons” at sites of forced demolition and eviction] for another attempted CCTV installation. To block it, a woman worker once again free-climbed the electric pole. Thanks to the raised voices of this woman at the top of the pole, Yongjugol residents, and citizen supporters, this installation was also unsuccessful. But there are likely to be further attempts.

Seeing

the women of Yongjugol asking for more time to become self-sufficient and be

able to relocate brings back the history of this place and how the state has

“dealt with” the people here. The process of shutting down Yongjugol will

become a testament to whether this history will be repeated or whether it will

find a new path to move forward.

*Original

article: https://ildaro.com/9826

No comments:

Post a Comment